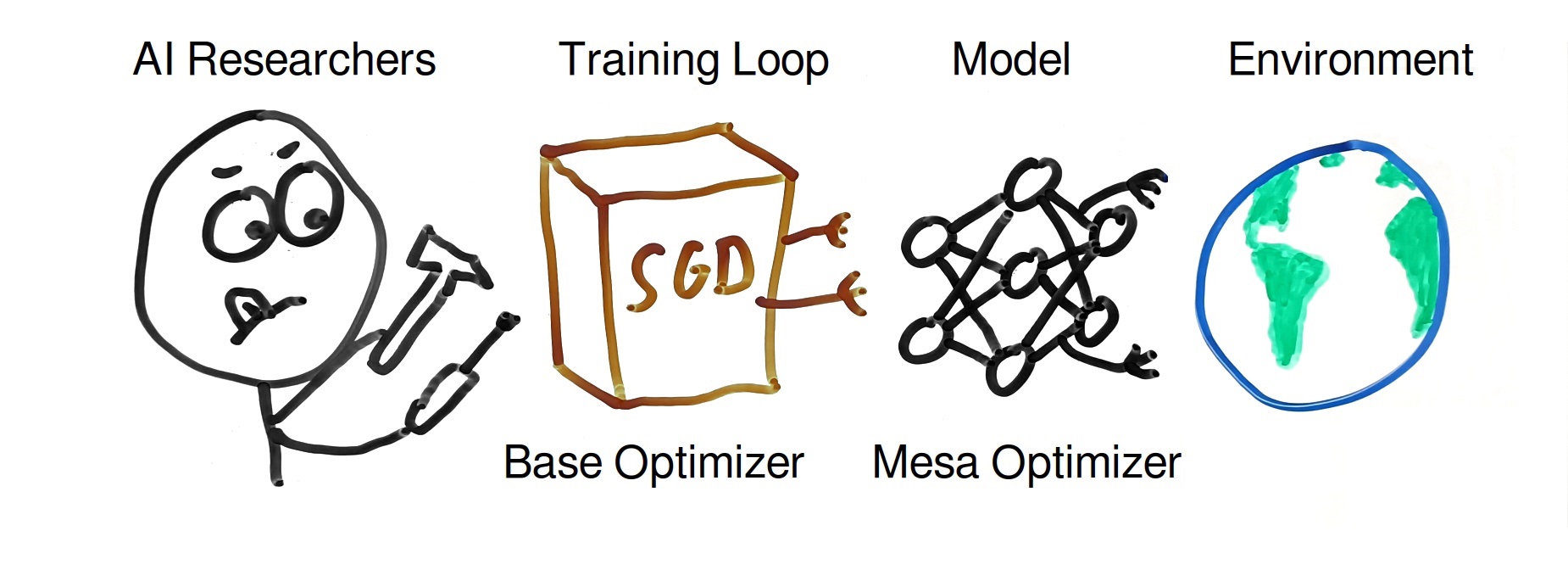

◎ Deep learning often involves human AI researchers tweaking some optimization process such as stochastic gradient descent, to train and output an AI model that is good at achieving some training target. Mesa optimization is the specific case where the trained model itself happens to be an optimizer, which then acts in the world and tries to move it to a certain state that's closer to its goal function.

◎ Deep learning often involves human AI researchers tweaking some optimization process such as stochastic gradient descent, to train and output an AI model that is good at achieving some training target. Mesa optimization is the specific case where the trained model itself happens to be an optimizer, which then acts in the world and tries to move it to a certain state that's closer to its goal function.

Basic

The term “mesa optimization” describes the scenario where an outer optimization process, such as the training phase in machine learning, create AIs that are themselves optimizers. As of today this does not happen in most cases, as the trained AIs usually end up behaving in some rather limited way that is not very close to deliberate optimization. However, there’s reason to assume that mesa optimizers will emerge from the field of machine learning eventually, because humans have reasons try harder and harder to get their training processes to create such mesa optimizers.

One example of mesa optimization is how evolution eventually led to humans, who are (in certain ways) optimizers themselves: we tend to deliberately shape the world so as to move it closer to our preferences.

This example also shows why the possibility mesa optimizers is concerning: humans are in many ways not aligned with the “goals” of evolution. Contraception is a prime example of this. If machine learning eventually leads to similarly strong mesa optimizers, coupled with similarly misaligned goals, this can lead to very undesirable outcomes.

Intermediate

A lot of the more “philosophical” thinking on the dangers of AI, such as that by Nick Bostrom or Eliezer Yudkowsky, focuses on “optimizers”, that is AIs that shape the world in ways that move it closer to some goal, utilizing a lot of optimization power. However, most AIs nowadays are probably not “optimizers”. Whether trained by reinforcement learning, or in a (semi-)supervised way, arguably they often just end up following some behaviours that “happen” to score highly on the training target. This doesn’t mean they have any kind of explicit internal representation of that training target, let alone they deliberately try to optimize for it. On the other hand, there clearly is some optimization involved in the training of AIs, often in the form of stochastic gradient descent (SGD). So usually there indeed is an optimizer at play, but the optimization tends to happen during training rather than during inference (= when the model is deployed in the real world).

Does this mean Bostrom and Yudkowsky were misguided in their worries, and trained AIs will be harmless, since they themselves are not optimizers? Unfortulately not, as this is where mesa optimizers enter the playing field. “Mesa” is simply the opposite of “meta”, so something like “one level down”. The idea is that a training process (in this context usually called the base optimizer) could potentially select for programs that themselves are optimizers (the mesa optimizer). Theoretically this makes sense: an agent that is actively optimizing for some training target has a good chance of being among the best agents when it comes to actually achieving said training target. Whereas non-optimizer agents likely perform worse in comparison.

However, the training loop is not some omniscient or omnipotent entity that just happens to find the best possible program or agent. It is still a relatively simple process, that usually starts with some randomized initialization of model weights, and then performs a greedy search process (such as SGD), iteratively improving the model weights. It’s unclear under which circumstances exactly such a process would actually find a set of model weights that would yield a mesa optimizer for any given initialization.

Yet, despite these uncertainties, there are at least two reasons to take this idea quite seriously:

- Even if currently training loops mostly don’t end up creating mesa optimizers and maybe even lack the capabilities to identify such programs in the vast multi-dimensional search space of model weights, we just need to look one level up: behind each ML training process, there’s a bunch of human researchers who constantly tweak the training regime in order to come up with the most capable possible models. These humans have an incentive to keep adjusting the training process until it will eventually be able to create mesa optimizers.

- Humans could be considered exemplary for mesa optimization: a simple outside process, namely evolution, has run an optimization on living beings, selecting inclusive genetic fitness, and eventually (quite misaligned, from the point of view of evolution) optimizers emerged in the form of humans.

One caveat to all of this is that the concept of an “optimizer” is difficult to define cleanly. And while it’s easy to think of optimizer-ness as a binary property, it’s probably more continuous, with some AIs being more and others less “optimizer-like”. Looking at the example of humans mentioned above, it’s not perfectly clear where on this optimizer continuum most humans would fall. Some individuals are optimizing for their goals much more than others, but practically all humans are investing some effort to shape the world in accordance with their preferences. So while many humans exhibit optimizer-like behaviour, we’re certainly far from perfect optimizers. But whatever may be true for humans, it’s easy to see that if we end up with some very capable mesa optimizer AIs, which are not properly aligned with our goals, this can lead to some very undesirable outcomes.

Advanced

- Risks from Learned Optimization: https://www.alignmentforum.org/posts/FkgsxrGf3QxhfLWHG/risks-from-learned-optimization-introduction

- Robert Miles video on mesa optimizers: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bJLcIBixGj8

- Mesa optimization: what it is, and why we should care: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/XWPJfgBymBbL3jdFd/an-58-mesa-optimization-what-it-is-and-why-we-should-care